Videos by American Songwriter

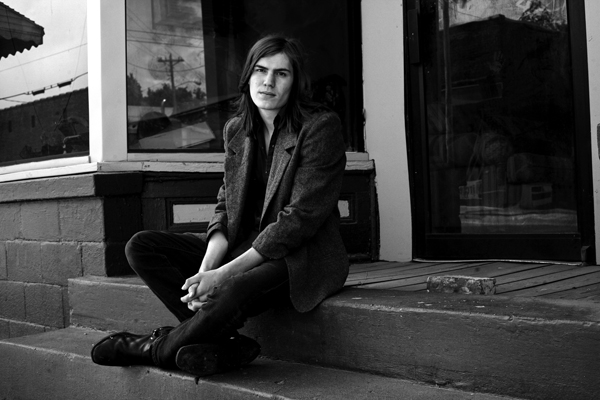

“I never really knew who I was hanging out with ‘til I got older,” says Dylan LeBlanc from behind a greasy forelock of light brown hair. LeBlanc grew up at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, one of the epicenters of soul music in the ‘50s and ‘60s, around hall of famers like David Hood and Donnie Fritts. “They would be cutting demos and doing sessions until one in the morning, so I’d make a little pallet on the couch and crash and stay there all week. Just nights after nights.”

It’d be easy to think that things have happened for Dylan LeBlanc because he came of age surrounded by a Southern legend. When he was 15, Jason Isbell, the fellow Muscle Shoal’er and one-time Drive-By Trucker, told him to get a bunch of books – Kurt Vonnegut, Tennessee Williams, Jack Kerouac – and pay attention to the language and study how great creative writers craft their work. “It’s really hard to get a grasp on what they’re writing, but I learned a lot,” remembers LeBlanc. “I don’t know if I came out on top or not.”

Dylan LeBlanc spent his early life in Blanchard, a rural outpost of Shreveport, Louisiana, in a doublewide trailer with his mother and stepfather, before moving to Muscle Shoals to live with his father, James, a staff writer at FAME, in his early teens.

“The songs weren’t good,” says LeBlanc emphatically about his early stabs at songwriting. “But it was really therapeutic. I always felt like I needed to be somewhere else and I could escape by writing songs.” A hauntedness pervades LeBlanc’s songs, much like Gillian Welch’s early work, and his music is trance-like, with the ghosts of old country and soul records filtered through his restless mind.

“I take things way too seriously,” says LeBlanc. “I have too many thoughts in my head that I can’t sleep… I escape into a different world and I imagine things. I should get up and clean the house or mow the lawn, little things that people do to keep themselves occupied, but I let my thoughts get away from me.”

Jon Tiven, a producer, heard LeBlanc at the Bluebird Café in Nashville in July 2009, and later told Geoff Travis, head of the London-based Beggars Group, about the young singer from Muscle Shoals. It’s not surprising to glimpse what Travis – who is often credited with discovering The Smiths and The Strokes and sits atop a notable indie empire – heard a year ago in the demos on LeBlanc’s MySpace page. The songs generally build around the heartbeat of one pentameter line, refrains like “Love is like water, and water gets rough,” “Tuesday night rain, Wednesday morning storm,” “Are you feeling alright? Are you feeling low?” The spirit world appears in the apparition of a girl’s touch in “Emma Hartley,” which LeBlanc says is personal, mixed with other observations that his mind soaked up “like a sponge” while he was writing.

The demos that LeBlanc began at FAME Studios, where he signed a publishing deal on his 18th birthday so he could use the recording facilities, eventually became the album Paupers Field, which was mixed by Trina Shoemaker at her barn in Nashville.

“She’s a wonderful, wonderful woman,” LeBlanc says of Shoemaker. “She came up with the idea for Paupers Field being the name of the record, because we were sitting out back, and just talking and smoking cigarettes. We were talking about how poor people bury their dead. And she was saying, ‘Have you ever been down to the paupers field in New Orleans?’ She said she used to go down there and it was a place where she felt like she could breathe and kind of calm down and feel good.”

But for LeBlanc, the shift from the comforting, familiar atmosphere of FAME wasn’t an easy step forward. Shoemaker, a Grammy Award-winning engineer and producer who has worked with Sheryl Crow and Emmylou Harris – who sings on the Pauper’s track “If The Creek Don’t Rise” and seals LeBlanc’s lineage to Gram Parsons and Bob Dylan – was tough.

“I was real intimidated by her at first,” says LeBlanc. “I walked in there and she was real businesslike, and she had a score for every one of my songs. Like 1 to 10, this song is a 7. After we broke that kind of relationship, it was almost like we had a brother-sister kind of relationship. We had these deep conversations on the back porch. We discovered that we were on the same page with a lot of things, like the way we think about life. After that happened, it was completely beautiful and the record just went amazingly.”

For LeBlanc’s precocious talent, the experience with Shoemaker would serve as just the beginning in a life full of new professional challenges. His coming-out at South By Southwest earlier this year was lukewarm, and a show at Joe’s Pub in New York this summer was panned in The New York Times. But what stands in the ashes of those disappointments is the stunning Paupers Field, as well as a shy and introspective 20-year-old. And for LeBlanc to have created a work of art at such a young age that resonates with so many people is ultimately his greatest achievement.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.