Videos by American Songwriter

The Origins of the Iconic, Enigmatic Anthem, In His Own Words

It’s one of the most famously mysterious songs ever to become a hit. It’s got enigma baked into it, which may be part of its lasting magic. Like Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood,” and other great though cryptic songs, it doesn’t fill in the entire picture, leaving it instead up to the listener to do that on their own.

All of its components enhance this dynamic of hypnotic mystery. There’s the swampy/mystic tone of the track, ethereal yet visceral, just acoustic guitars, bass, and conga with no drums. The vocal is delivered as if from a storyteller spinning an ancient mythic tale, not performing as much as testifying, and in language that resounds like coded poetry. We’re in motion the entire time, days are passing, and the heat is relentless. Elemental symbols are everywhere like images from a perplexingly real dream – a dry riverbed, appointed with plants and birds and rocks and things, and incessant sound.

And, of course, there’s that mysterious horse, the one with no name, which did forever force the question: Why? Why didn’t anyone name this horse?

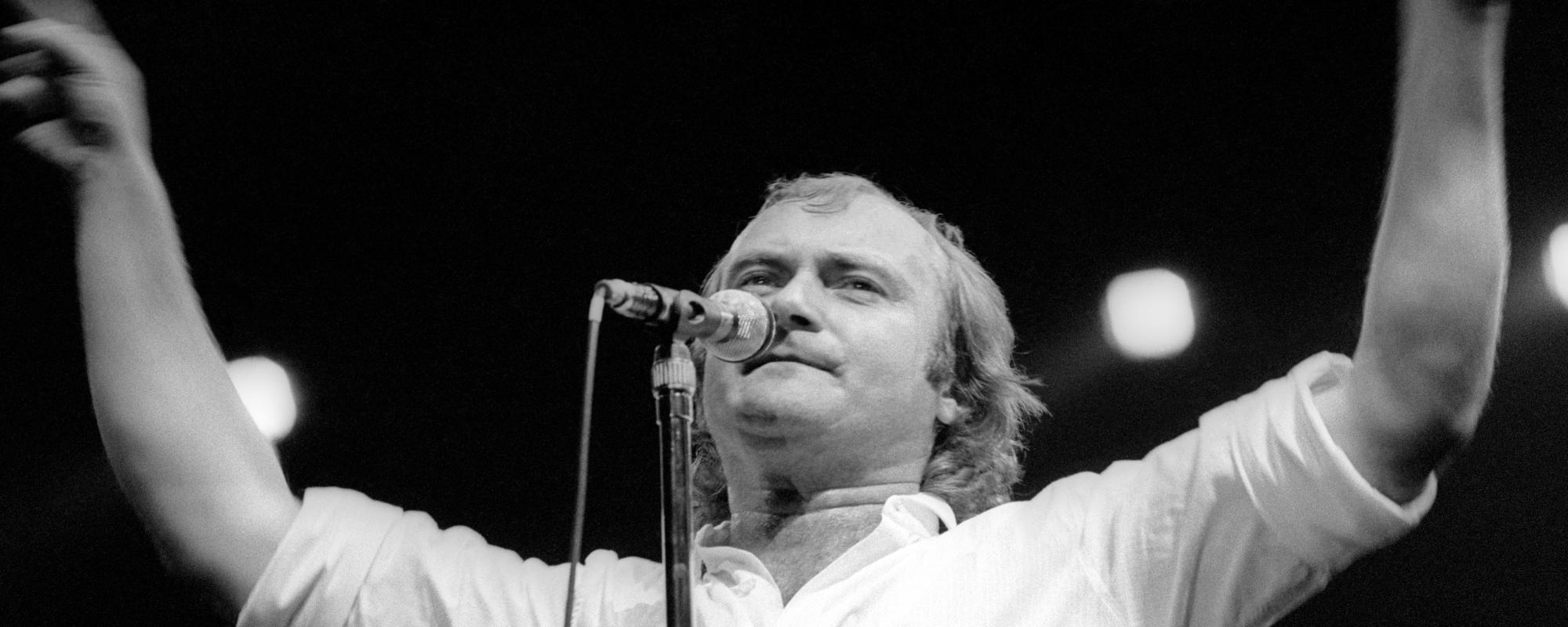

In search of answers, we turned to the songwriting source himself, Dewey Bunnell, who spoke to us on the phone last week, the final week of March 2020, at the start of the mandatory stay-at-home orders in California.

Dewey was one-third of America, with Gerry Beckley and Dan Peek. All three wrote songs, played guitar, and harmonized beautifully. Gerry wrote “Sister Golden Hair,” and “I Need You.” Dan wrote “Don’t Cross The River,” “Lonely People” and others.

And Dewey’s the guy behind some of their most enigmatic and yet anthemic songs, including “Tin Man,” “Ventura Highway,” and “Horse With No Name.”

Peek left the band in 1977, at which time Dewey and Gerry elected not to replace him, but to go out as America on their own, along with a backing band. “We’re the Fab Two,” as Dewey said.

He was at home in Los Angeles when we spoke. When not on the road, he and his wife split their time between this house and one in the Northwoods of Wisconsin. They’ve got many cats, a dog, and a horse. The horse’s name, he said, is Noname.

America was just about to start a two-week run when the virus panic escalated and forced them to change their plans. So before delving into the roots of this mysterious song, Dewey spoke about the impact of this stay-at-home policy on life in the Fab Two.

“Yes, we are on lockdown,” Dewey said. “We made a decision on the evening of March 11, after flying out to Columbus, Ohio for a show in Huntington, West Virginia. We had our gear, the band, and crew in a hotel, and realized we’d been putting our head in the sand over this deal. We were facing nine shows in all over that two-week period, and we realized that we had better pull the plug on this for a while, to see how serious this is getting.

“We flew home the next day, March 12, and have been in our homes ever since. The day after we flew home, the national emergency was announced, and then everything started caving in. All our other shows were postponed.

“We feel like we made the right decision. We made a public announcement to our fans that the shows had to be postponed. After all, our demographic audience is in their 60s, or 60-plus. So the whole thing added up to us being part of the problem, instead of the solution. We’re glad that we did it at the end of the day.

“Right now doing okay. I’m here with my wife. We’re doing jigsaw puzzles, watching TV, eating too much. We’re probably spending more time with our pets. We have a horse and a dog and four cats. You look at the upside, right?

“Plus, it’s a shared experience. Everybody is doing it. We know that. It’s one of those times in our history that we’ll remember.”

The sad news of the death of producer-songwriter Adam Schlesinger from the Coronavirus hit Dewey hard, as America had worked closely with him.

“We are mourning the loss of Adam Schlesinger,” he said. “He was a friend, and he produced our Here & Now album back in 2007, along with James Iha. It’s really been a shock. We are big fans of the music made by Fountains of Wayne, and we did some shows with them back then. It’s very sad news.”

There is one unexpected positive this long-time touring musician discovered in the midst of this ongoing solitude: a rare sense of peace, something he hadn’t known in decades; a license to be still, with nowhere he needed to go.

“My mind and body,” he said, “seem always geared up for travel, motion, moving, getting somewhere, packing a suitcase. One of the strangest things about this quarantine is that this is really an abrupt stop. Not a bad abrupt stop; it’s a nice new experience.

“But it’s a new experience, being here. It’s brought that feeling to a stop, that feeling that I’ve got to get ready, got to go in 48 hours, got to catch a flight, got to get my laundry done.

“Instead of all that, I can just be.”

“Horse With No Name”

It’s a song that came quickly, as he remembers, “all in one fell swoop.” So immediate was its creation that Dewey wasn’t sure what he had, and even if it was worth recording, or should be relegated to the novelty song bin. Never did he consider it hit material, or a song that would become a rock standard and for which he’d be famous forever.

Yet “Horse With No Name,” which vividly introduced the barren desert landscape of the southwest into popular song long before The Eagles, James Taylor, and others did it, was never easy to understand. Even for its songwriter. From its inception, it seemed to take on a life of its own. It’s something which hasn’t ever stopped and extends to now.

Released in late 1971 overseas and early 1972 in America, it went to the top of the charts. But never was it a fly-away hit, beloved during the season of its creation but ultimately forgotten and abandoned. Instead, it’s become one of those songs with an appeal that has incrementally expanded over the years. Never has it been absent from radio, the culture, or our memories, for long.

That it’s made a lasting cultural impact is undeniable; evidence of this is everywhere always, most recently only days ago, in a viral video posted by a couple in quarantine in Amsterdam. Mara van Nes and her boyfriend Sem Jonkers used their isolation creatively and acted out the song in their own way.

Rather than oppose such comic usage, Dewey and the band fully embrace it and posted the video on the official America fansite, which propelled it on its viral flight.

The origins of this iconically mysterious tale of the American Southwest by a band named America began, as did the group itself, in England. Bunnell, Beckley, and Peek were all bonded by heritage and location, the sons of airmen in the U.S. Air Force stationed in London. It’s there that this story takes place.

DEWEY BUNNELL: The song was borne out of pure boredom. I had just graduated high school in London, and my family moved up to Yorkshire, where my mother was from. I wanted to stay in London, so I moved into the home of a friend and his family.

America had signed with Warner Brothers and had a record out. We had been recording and were in full gear, playing shows and recording.

I wrote the song alone in this guy’s bedroom that I shared. I wrote it all in one fell swoop. I wrote it in a couple hours.

I didn’t question the song. I felt like it suddenly appeared, like waking up in a dream. It was a dream of being on a horse and realizing that I don’t even know the name of this horse. And there was serious heat. I remember getting sunburned severely as a kid and it was on a beach. It wasn’t in the desert. But I guess in my mind’s eye, I was thinking, “I’m on this horse, I’m going somewhere, who knows where? I don’t know the name of the horse. Maybe I didn’t even have a hat on.”

Do not underestimate the concept of trying to find rhyme. “I spent three days in the desert sun, my skin began to turn red, I was looking at a riverbed.” Had it been the other way around, I probably wouldn’t have come up with the sunburnt thing.

I remember that I did have visuals for that riverbed. I have a picture in my mind of my brother and I when we used to hike around the desert in the sagebrush. This was when my dad was stationed at Vandenberg Air Force in California, a base that was out in the middle of nowhere, up by Santa Maria, California. We would hike around that a lot.

There were a lot of dry gulleys. It was more of a California terrain that I was referring to than the Arizona-type desert. But I do remember my brother and I always hiking out to this one spot and down this dry riverbed. Up on the side of the dry walls, sometimes there’d be holes dug in there by animals. I remember we found some owls in one of those holes in the bank of the dry riverbed.

There’s a lot of motion in the song. That’s something I can’t get away from in my songs. I’ve had a lot of travel experiences and those are the things that get branded in your brain. There’s motion, and there’s a progression. And by the end of the song, I let the horse run free. I wasn’t sure why, but it seemed right. It’s seemed it was time to let go of the horse and to move on.

If there was a next verse, it probably would have been, “Getting in a boat.” But the song was already long enough.

It wasn’t called “A Horse With No Name” though. It was called “The Desert Song” then. And it was just thrown into a pile of other songs. When I first brought it to Gerry and Dan, and we were playing it, I really thought it was almost a novelty song.

I wrote it in open-D tuning. I started experimenting with that after hearing. David Crosby and Joni Mitchell, who were using open tunings. And we were definitely immersed in their songwriting.

It’s open-D tuning, where you tune the Es down to D. But I did a little different thing where I tuned the A all the way down to E.

That was the only time I ever used it. I was just sitting there tuning it down and it sounded good. I was bored, just trying to make different sounds come out of that guitar.

The first album was already in full swing. We hadn’t picked a single yet, but we were keying in on “I Need You” (by Gerry) to be the first single. At that time, you wanted a single to lead the way with your album. “I Need You” was certainly going to be that. It was a great song, almost a standard. It still is. It was covered by lots of people over the years.

So we had our single. But Warner Brothers said, “Have you got any more?”

We had four songs at that point, and we went to a little studio to demo them, which was in the Islington farmhouse. That’s where we recorded the first version of “The Desert Song. “

When Warner heard it, they said, “Hey, we really like that. Let’s record that.”

At that point, our recordings were just the three of us sitting around a room with our voices and our acoustic guitars. Dan or Gerry would play bass. When we got into the studio, there was some overdubs. We put conga on this, and Gerry played the solo on a 12-string guitar.

Ian Samwell produced the record. It is very close to our demo; the sound was there. But Ian was certainly the overseer, and he had a big impact.

I still didn’t have the title. At that time, I would just name the songs anything I liked. I had “Moon Song,” “Rainbow Song,” “Pigeon Song.”

But as we were honing this song down, Ian said, immediately “Well, dude, you must call this ‘Horse With No Name.’ ”

And I said, “Sure, that’s fine.” I didn’t blink.

As it was, it did have a better ring than “The Desert Song.” Plus he pointed out that there was apparently an opera called “Desert Song.” We didn’t want to have any confusion.

I remember the first time we played “Horse With No Name” live, we were opening for Traffic. It was still “Desert Song,“ then, and my mother heard it for the first time. She said, “I do like that horse thing.” Other people, too, said, “That song about the horse was a good one.”

I am glad we used that title. So many people think it’s mysterious. Here it is, just about 50 years later, and people still say, “I feel so sad for that horse. Why didn’t you give that horse a name?” They actually get emotional about it.

But I found mystery is good for a song. I think it’s good to leave something to the imagination of the listener. It’s that way in a lot of songs. I’m very visual, and I like to create a narrative that is visual. That’s part of my life, because nature, and the outdoors, all of it was really important to us. Because of moving around a lot in the military, the one constant my brother and I had was always to go out hiking, going to the woods, to the swamp, the desert, whatever the environment of outdoor life was that we had. Because we didn’t know any other kids. So it was a great sense of solace.

Plus we were very excited and curious about plants and animals – as in the song, “plants and birds and rocks and things.” We would catch snakes and lizards. I like to create that imagery of outdoors. Then you can fill in all the blanks and maybe see the picture in your own mind.

I loved the desert. Moving around all the time, I wasn’t used to it. My dad’s older brother lived in New Mexico. We’d driven across the Southwest one other time, and I remember long stretches with the vanishing point, all those iconic classic looks of the desert. This was in the Sixties and things weren’t that built up. There were billboards and stuff, but it was still very vast…

I’d seen pictures of cactus. It seemed so exotic to me. So getting out of the car at rest stops or just pulling off the side of the road, walking out in that and just having that heat hit you, it was something. The first time I ever saw a wild cactus was amazing. I just loved the desert. It left a huge mark on me. It still does. There’s that whole concept of being isolated and alone with your thoughts. There’s a feeling of comfort when it’s just you.

Some of the lyrics of “Horse With No Name” were a little clumsy in a lot of those lines. I wrote that song in maybe two hours at the most, and most of the lyrics, I didn’t even adjust after the fact. I was new to songwriting and this was just pouring out of me and that was the theme I wanted to try and project that imagery.

The grammar is based solely on almost a character’s voice that would convey that a little better than a proper-sounding voice. That line “there ain’t no one for to give you no pain.” I’ve never used that kind of dialect. We lived in Biloxi, Mississippi and there was occasion with a deeper Southern accent and then in Nebraska, you might get some farmer guys that might say, “Ain’t no one for to,” or something like that. It was purely another colorful way to express something, like taking on a character.

But that kind of language works well in a song. Like “ain’t got no satisfaction.” It conveys something a little more practically because it can sound clinical or sterile when you really put together a perfectly well-constructed sentence without some emotion in there.

So this is all part of this lineage of this song after all this time. I’ve read and heard and been told many things over the years about it, and it’s always great to think that it came as a little seed sitting in that bedroom once, alone, to be able to communicate things to people that they relate to. I’m really very proud of that.

It’s true the song got banned from radio at one time because people said it was about heroin, which sometimes was called ‘horse.’ That was news to me. Living in England, I don’t ever recall that term. I think it was more of an American term. It might have been smack or dope or H.

I have to believe some junkies out there listening to it went, “Hey man, this dude is like me. He’s one of us!” Everybody has their imagination about what bands have been doing. Plus those were the days when drugs were a little more rampant and stuff was going down.

There’s all kinds of funny things that people thought it was about drugs.

Sure, there was pot smoking and stuff going, and we were young guys experimenting. But there was no heroin or hard drugs or anything like that going on. One of my favorite quotes is from Randy Newman when he said, “That song is about a guy who thought he did acid.” We always like quoting Randy on that one.

Sure, we had fun in the pubs. But as far as being intoxicated, I’m intoxicated by writing songs. That, in and of itself, is a meditation. When you get full bore into writing a song and creating that imagery lyrically, that is a drug. And we’ve been getting a buzz off this song for decades now. “A fly with a buzz.”

“You’re inspired and intoxicated by the theme of the song, or the process of writing a song. You’re creating this thing out of nowhere that is going to ultimately have its own life. You do it for yourself to some degree, but you’re obviously presenting it to the world and you’re hoping that people enjoy it.

It feels great to have written songs the whole world knows. It’s something you don’t have any control over. It’s one of those strange occurrences in my life, obviously. It’s something that never goes away.

Are you a songwriter? Enter the American Songwriter Lyric Contest.

“Horse with No Name”

By Dewey Bunnell

[Verse 1]

On the first part of the journey

I was looking at all the life

There were plants and birds and rocks and things

There was sand and hills and rings

The first thing I met was a fly with a buzz

And the sky with no clouds

The heat was hot and the ground was dry

But the air was full of sound

[Chorus]

I’ve been through the desert on a horse with no name

It felt good to be out of the rain

In the desert, you can remember your name

‘Cause there ain’t no one for to give you no pain

After two days in the desert sun

My skin began to turn red

After three days in the desert fun

I was looking at a riverbed

And the story it told of a river that flowed

Made me sad to think it was dead

I’ve been through the desert on a horse with no name

It felt good to be out of the rain

In the desert, you can remember your name

‘Cause there ain’t no one for to give you no pain

[Verse 3]

After nine days I let the horse run free

‘Cause the desert had turned to sea

There were plants and birds and rocks and things

There was sand and hills and rings

The ocean is a desert with its life underground

And a perfect disguise above

Under the cities lies a heart made of ground

But the humans will give no love

I’ve been through the desert on a horse with no name

It felt good to be out of the rain

In the desert, you can remember your name

‘Cause there ain’t no one for to give you no pain

From “Horse with No Name,” by Dewey Bunnell.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.