Videos by American Songwriter

When writing fiction, budding authors are often encouraged to use language that animates a situation. To animate means to infuse something with life. For example, “Daniel peeled the orange and left the skin on the counter” is a perfectly acceptable sentence, one that conveys an event in terms that are easily understood. But if the same event is reframed as “Daniel abandoned the orange peel in the formica desert,” the action takes on a little more significance. Since Daniel “abandoned” instead of “left” the peel “in the formica desert” instead of “on the counter,” the reader might feel that the action carries more consequence, or that the orange peel has a larger place in the story than previously thought. Or that the author was high as a goose when he sat down at his laptop that day.

Unlike fiction, songs lyrics are usually structured in a way that limits the amount of words and syllables that can be used in a particular line or verse. In addition to this, a rhyme scheme often dictates what particular vowel sounds must be, usually at the end of a line but occasionally in the middle or the beginning of it, as well. A significant amount of time in the songwriting process is dedicated to finding the perfect word, the one that not only conveys the right meaning but also fulfills a line’s syllabic requirements while fitting into its rhyme scheme. This particular struggle has been known to drive full-grown men to tears and full-grown women to Oprah, ruining friendships and debilitating national economies along the way.

While this wrangling with words is often necessary and unavoidable, it is important to remember that songs do not draw their primary strength from words. Melody is the soul of a song. A melody animates a lyric, bringing it to life in a way of which even the most perfect verb or modifier can only dream.

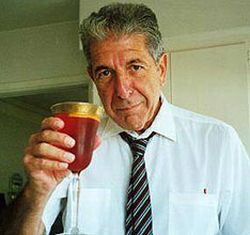

If you are not already familiar with it, take a moment to listen to the opening verse of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah:”

Well I heard there was a secret chord

That David played and it pleased the Lord

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

Well it goes like this, the fourth, the fifth

The minor fall and the major lift

The baffled king composing hallelujah

Granted, these are not exactly throw-away lines that any of us could just knock out over a cup of coffee. This is Leonard Cohen, after all. But in the context of the entire song, these lyrics are merely setting a scene. Still, and in spite of the fact that nothing particularly significant seems to be happening yet, this is one of the effective stanzas of music written in the last fifty years. It’s not just the words and it’s not just the melody; it’s how they interact.

Melodies can work in an infinite number of ways. “Hallelujah” is particularly wonderful because the melody is as conversational as the lyric. The first two lines:

Well I heard there was a secret chord

That David played and it pleased the Lord

… are set to the same two or three notes, a simple arrangement that establishes them as a singular thought, Cohen’s opening salvo. Then he takes a soft jab:

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

… and the melody inverts, shifting upward ever so subtly, the musical equivalent of a raised eyebrow.

Well it goes like this, the fourth, the fifth

The minor fall and the major lift

Now Cohen is gaining confidence, needling his subject about the very thing he just acknowledged that she doesn’t care for, and the melody rises up with him. (The fact that Cohen is actually executing the musical movement being described in the lyric is slightly beyond comprehension and worthy of an entire blog unto itself.)

The baffled king composing Hallelujah

Cohen finishes the stanza by connecting himself to the Biblical king at the beginning of the verse, establishing the main lyrical metaphor with the highest passage of notes yet heard in the song. It feels exasperated, heartbroken and resigned all at once.

Great lines stay in your head for awhile, but great melodies get into your heart forever. The next time you sit down to write, pay special attention to the relationship between your words and melody. Are they supporting each other? Do they interact? Is their relationship moving your song forward or holding it back? In answering these questions, try to remember that songs are meant to be sung, not recited. If you find yourself at a loss for the perfect word, it might be a good time to look for the perfect note.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.