Videos by American Songwriter

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2007 issue.

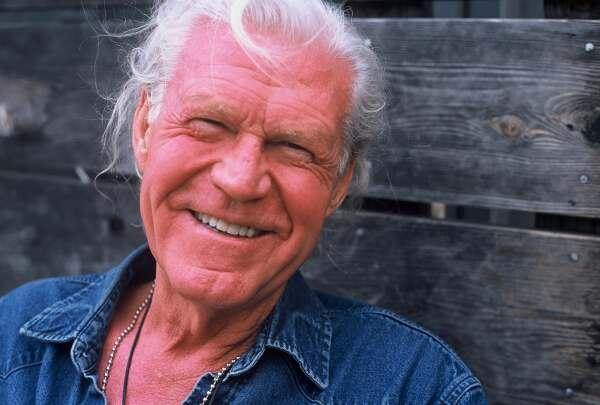

Here on the porch outside John Carter Cash’s studio in Hendersonville, surrounded by woods just north of Nashville, Billy Joe Shaver seems right at home. It’s not just because he cut his latest album, Everybody’s Brother, here. Really, no matter where you put him, it’s obvious that he’s never been a city guy.

His hair has gone white. His face is etched deep. His right hand is short a couple of digits. But then you already knew that, because he told you about it, back in ’87…

My hands are both callused and worn

They’re some fingers that are gone off of one

I’m rough as a cob but I do a good job

Yeah, I am a hard working man.

– “Hard Workin’ Man”

The thing is, even though he acts a little awkward when asked to talk about himself, that’s pretty much all he’s ever done through his songs. He was born dirt poor. His father was a dangerous man; abandoning his family shortly after Billy Joe was born was probably the best thing he ever did for his newborn son. His mother tried to provide, but after a while she left him to her mother’s care in Waco and disappeared as well. We know this because Billy Joe wrote about it too…

My grandma’s old-age pension

is the reason I’m standing here today.

– “I Been to Georgia on a Fast Train”

That pension, plus hard work picking cotton that began when he was 12 years old, lifted Shaver out of that world and into the Navy the day he turned 17. After that he worked in rodeos, got into fights, drank too much, hitched out to Los Angeles and eventually wound up in Nashville with a head full of songs he’d never bothered to write down or commit to tape. Somehow he still managed to catch Bobby Bare’s attention, which led him toward a friendship with Waylon Jennings that began when the irascible country star recorded an album that consisted almost entirely of material from the young and unknown Shaver.

That record, Honky Tonk Heroes, put Billy Joe on the map in ’73. Once there, though, he kept wandering the back routes rather than joining the traffic down on Music Row. Elvis Himself covered his songs; so did Kris Kristofferson, a sign of powerful respect from the archetype of modern alternative songwriting. Yet Shaver remained elusive. His first wife, Brenda Joyce Tindell, divorced him. They remarried, divorced again, and then did the same one more time. He seemed incapable of being faithful or forgiving himself for his transgressions. He sank into heroin addiction. His son, Eddy, a guitarist of enormous potential, followed in his father’s footsteps and died on New Year’s Eve 2000-a year after Brenda and Billy Joe’s mother both succumbed to cancer.

Nothing Shaver did, in other words, reflected any ability to make wise choices in life. And yet sorrow made him wiser, never leading him to the point of learning the obvious lessons and tempering his ways, but definitely opening his reflections of life to a more timeless perspective. More like the woods in these Tennessee hills.

That helps explain the sound of Everybody’s Brother: It’s unpolished even by Shaver’s usual standards, with bare instrumentation, not much electricity and rough spots in his vocals like knotholes on a pine wall. As for the songs, they’re typical of his work, with the chords and melody kept as simple as possible to let the words ring clear.

Those words focus mainly on the two subjects that Shaver has most favored through the years, though his perspective on both has changed. He addresses love now with the kind of affection that only time can bring: “She’s the mother of your children,” he marvels over the slow-dance sway of “To Be Loved by a Woman.” “Thank God she can’t leave you alone.”

It’s salvation, though, that dominates Everybody’s Brother. All of Shaver’s albums touch on this, though never with the grit he musters here. “Jesus Is the Only One Who Loves Us” offers snapshots of people living on the underside of life, from stumbling drunks to guttered junkies, each one followed by a chorus that reminds us that their Savior loves them still. And on “The Tough Get Going,” a more secular meditation, he doesn’t forget to insist, “Jesus Christ is the toughest man alive.”

Then there’s the title cut, on which the wheezing drone of a pump organ transports us into the primitive church that lives somewhere deep in Shaver’s scarred heart. The words in this song, more than any other Shaver has written, put this matter of faith on the table as a matter of urgent attention. They warn of damnation through apocalyptic images drawn from both Billy Sunday and the young Bob Dylan.

Frankly, it’s a little scary. And that doesn’t bother Shaver one bit. “Being a Christian, I can’t get away from that,” he says, grinning perhaps at the irony of the idea. “One of my songs on there is ‘If You Don’t Love Jesus, Go to Hell.’ And I sing a Johnny Cash song with Kris Kristofferson…‘You’re So Heavenly Minded, You’re No Earthly Good.’ I should have written that one myself …”

Shaver laughs, as he does every minute or so in conversation. “I don’t care what people think. They think I’m using Jesus for something. Well, back when I first came to Nashville, the very first song I had recorded was ‘Jesus Christ, What a Man,’ by the Oak Ridge Boys. And every album I’ve done has at least one or two songs about Jesus on it. Waylon Jennings called me a Bible-thumper because back then, it wasn’t popular. But now that it is, people say, ‘Man, you’re riding Jesus.’ What they don’t know is that it’s a burden. I have an obligation to do that. We all do.”

Like many believers, Shaver can pinpoint the moment of his salvation. It’s easy, in his case, because he marked the event with a song. “That’s when I wrote ‘Old Chunk of Coal,’” he remembers. “I was out on a cliff at the narrows of the Harpeth River [in central Tennessee], close to Kingston Springs. I’d been doing everything in the world, driving my family crazy. I was about to die. There was no moon-a cloudy night. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. But as I was coming down from that mountain at about four in the morning, I sang the first half of that song and got it into my heart. And I asked God to forgive me for what I’d done…I was the king of the sinners, and yet he forgave me.

“Then I got my family….boy, they were mad, and loaded them up and moved out to Houston. If I’d stayed in Nashville, it would have been impossible for me to clean up. But in Houston, I prayed hard. I quit smoking, drinking and doping. I dropped down from about 230 pounds to 150. And one morning I finished the second half of that song.”

In “Old Chunk of Coal,” Shaver predicts that he’s “going to be a diamond someday.” Truth be told, that transformation remains a work in progress-but this absence of resolution invests his faith with a real world quality that separates his perspective from the holier-than-thou smugness of much Christian music nowadays. “Well, I’m coming from a different direction than that,” Shaver says, with a shrug. “But as far as I’m concerned, if you write anything about God, you can’t go wrong. A lot of times people will say, ‘That guy is in church just to be seen.’ Yeah, but he got into church, and that’s fine with me. And if they keep on with it, like my grandma used to say, they’ll get it done for real.”

The sound, like the message, of gospel music has become a defining quality of Shaver’s latter-period output. He insists that it’s because the music of the church is real. “I’m pretty sure that the same guy that wrote ‘How Great Thou Art’ also did …” And here, Shaver, perhaps confusing songwriters Stuart K. Hine and Stuart Hamblen, starts to sing Hamblen’s “I Won’t Go Hunting With You, Jake,” with its references to “chasing women. Put them hounds back in that pen. Stop your silly grinnin’.”

“What a wonderful song!” he says, shaking his head. “I ain’t written one that good yet. It’s real, because he came from one end to the other. It’d be hard to top that or something like ‘Amazing Grace’ and a lot of the old African-American gospel, because they were new and young into Christianity, so they were deadly honest.”

Honesty is the key to Billy Joe Shaver, who is probably the most candid songwriter alive. Whether chronicling the profane or the divine, he writes only from experience. A lot of this comes from his strong sense of recall; his memories, stretching back to hearing black kids singing along to Jimmie Rodgers records, completes the feedback loop that began the blues nourishing the Singing Brakeman’s soul. Always, he wrote without thought of the consequences. Even when his wife left him in a fury after hearing the brutal candor of his song “Ragged Old Truck,” Shaver remained incapable of artifice.

“I can’t allow that to happen,” he insists. “I made a deal with myself a long time ago that I would always tell the truth in my songs. It’s like you hear from a lot of rap music. I mean, some of it’s great; it’s poetry off the streets. But some of these guys are coming out of college. They have nice homes. They’re not streetwise. I can always tell which ones are real. That’s how I’ve always written. I’m just blessed that way.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.