If I’ve heard it once, I’ve heard it a thousand times: “Music is a language.”

Videos by American Songwriter

“Wow!” I used to think, “Great! Now show me the dictionary so I can stop aimlessly fishing for notes and know what the hell I’m saying.”

Well, slowly, painfully over the years, I learned my lesson. I know where they’re headed next – down the primrose path of music theory. And I know what’s waiting there: a dead end.

Finally, after a lifetime of waiting, I decided to write my own dictionary of musical meaning. And what I discovered is that you have to write your own. That’s what all the readers of this column have been doing since March 2012: listening to hit songs from multiple angles, soaking up the significance of rhythm, harmony, phrase arcs, interval color, scale tone moods, and more.

So now that we have our dictionaries together, the time has come to use them. Enter melodic rhyme.

Melodic rhyme is as simple as “shake and bake” or “rock and roll”: similar sounding groups of notes placed close enough together to be noticed. In previous columns we’ve learned a few melodic “words.” Melodic rhyme is the glue that binds them together in meaningful phrases. But therein lies the magic, for rhyme is the secret sauce that gives melody its emotional punch.

Like poetic rhyme, melodic rhyme often occurs at the ends of phrases, a technique that’s been around for ages. Think of those soaring leaps in Puccini’s aria O Mio Bab-bino Ca-ro / mi piace, è bel-lo bel-lo…” Now fast-forward to “Somewhere Beyond The Sea / somewhere waitin’ for me.”

Notice how end rhymes anchor the interval colors in memory. So do internal rhymes (rhymes within the phrase). The first leap in “Beyond The Sea” occurs on “Some-where.” When we hear the second and third leaps (on “The Sea” and “for me”), they rhyme with the first, connecting all of them into a musical sentence that can almost be translated into plain English.

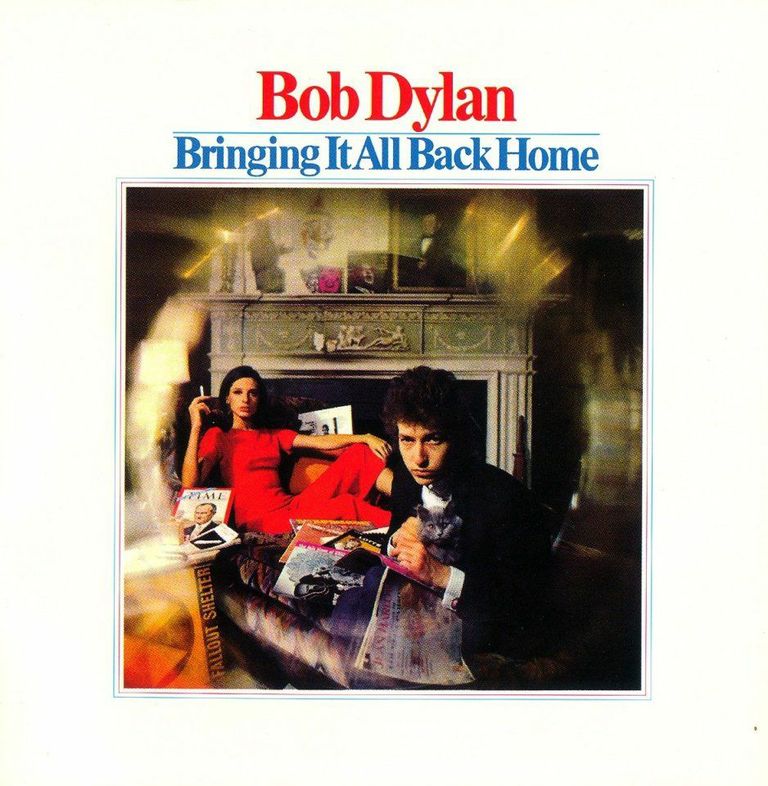

Composers often use internal melodic rhyme the way poets use alliteration. For example, listen to Bob Dylan in “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The alliteration is in the melody, not the lyrics:

“And if you hear vague traces of skippin’ reels of rhyme, to your tambourine in time, it’s just a ragged clown behind, I wouldn’t pay it any mind, it’s just a shadow you’re seein’ that he’s chasin’.”

For another example of internal rhyme, consider “Amazing Grace.” First, think of the two upward leaps on “A-ma-zing Grace.” Our interval dictionary says that the first leap (a rising perfect 4th) means “bold, assertive,” and the second (rising major 3rd) means “joyful, warmly tender, loving.”

On “…how sweet the sound,” the melody descends, retracing its steps with a rhythmically accented melodic rhyme. The intervals are emotionally neutral descending major 2nds, so the meaning has more to do with scale-tone mood than interval color: “Re” falls to “Do,” implying submission to a higher power (the tonic), and “La” falls submissively to “Sol” – that is, from “joy” (La) to “faith and hope” (Sol).

The interval between the top and bottom tones is a joyful major 6th. The heavily accented bottom tone is Sol, the symbol of faith. These soulful rhymes blend with the rainbow phrase contour to express a simple declaration of faith, hope, and joy.

In poetry, end rhymes tend to be more significant than internal rhymes because we instinctively expect a phrase to come to the point at the end. More important, by rhyming, the final word hearkens back to the previous line, causing the phrases to overlap one another in memory, forging an alloy of imagery and feeling impossible in ordinary prose.

End rhymes also help to explain the storytelling power of a good melody. A simple example can be found in “Here, There And Everywhere” (Lennon and McCartney): “and if she’s be-side me I know I need nev-er care / But to love her is to need her ev-’ry-where.” Here, the words rhyme, while the harmony shifts from minor to major, implying that love conquers all.

And let’s not forget the relationship between rhyming and memory. Nursery rhymes help children remember their ABCs, jingles help us (force us?) to remember products, and rhyming lyrics help us remember songs. For tunesmiths, the lesson is clear: If you want to write a memorable hook or a hit tune, marshal the forces of end-rhyme and internal rhyme.

Finally, research has shown that people tend to believe rhyming statements more than non-rhyming statements. This is equally true of melodic rhyme – nay, not just true, but ten times true (“Measure For Measure,” Act V, Scene I), which suggests why, for example, the surreal vision of “Mr. Tambourine Man” is so moving and convincing.

Melodic rhyme is by far the most powerful concept we’ve discussed so far, and there’s much more to say about it, so be sure to e-mail info@americansongwriter.com for the e-book (number five in the series). As always, it’s free.

In the meantime, just remember that the answer to the title question is an emphatic “Yes!” But only if you want to write a hit song.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.